The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly of Annuities

As we enter what has historically been the most volatile months of the year for the stock market (September & October), we should probably brace ourselves for the inevitable annuity advertisements as they become more prevalent on TV, radio, and social media. (For a quick reminder of how volatile September can be, check out our blog from 2018: How to Enjoy September). Insurance companies realize fear can be a powerful motivator and likely have these pitches queued up and ready for the next market correction.

Very often, these products are pitched as a “personal pension” or “money guaranteed to go up and can never go down.” In theory, this can be true with some annuities. While this sounds like a great concept, the most skeptical among us might react with “If it’s too good to be true, it probably is.” And the devil is always in the details. Given this backdrop, it’s a good time to revisit some basics of annuities and provide some perspective. This perspective can easily be summed up by the title from the classic 1966 western starring Clint Eastwood, The Good, The Bad & The Ugly.

What is an Annuity?

Let’s first start with defining an annuity in the most basic terms. An annuity is a contract signed with an insurance company, usually to exchange a substantial sum of money from the annuitant (the customer) for a promise of future payments from the insurance company. There are many, many variables that get applied to this agreement: the underlying investments, the time period for payment, when you start receiving payments, who might get paid if the annuitant dies, etc.

Example: A 60-year-old male who wants payments to start immediately might write a check for $250,000 in exchange for lifetime monthly payments. How much will that buy him (according to immediateannuities.com)? About $1,079 per month for the rest of his life, or a payout of about 5.2% per year. Not bad right? It seems he has a guaranteed stream of income. Well, read on for The Bad, The Good, and The Ugly.

How Do Annuities Work? The Bad, The Good, and The Ugly

THE BAD

Lack of Liquidity: Once you sign up for most annuities, you’re turning over a substantial portion of your nest egg in exchange for the promise of future payments. However, in most cases, once your money is with the insurance company you no longer have easy access to it, and neither do your heirs. If an emergency comes up and you need your money back, the contract usually stipulates onerous “surrender charges” of up to 10% in the first year of the contract. This surrender charge usually goes down each year for the next 7 to 10 years until it lapses. The biggest risk with some immediate annuities is early death: if you purchase an annuity and die unexpectedly early, your heirs could be left with little to nothing. Of course, there are some contracts with death benefits, but this rider (additional option) can be much more expensive than simply buying a term life insurance policy.

Expensive, Conflicts of Interest: Some annuity salespeople say “you don’t pay me, the insurance company does.” But one would be mistaken to think the insurance company would offer the same income benefits on their annuities if they didn’t have to pay the salesperson 3% - 5% (some as much as 6%) of the contract value or more up front. In addition, many annuities have annual fees (in addition to the commission paid) that can range from 1% - 3% per year on the contract value. So should you really ask an annuity salesperson for advice on whether or not it’s a good idea to buy an annuity if he or she has a large payout hanging in the balance?

Limits on investment returns in exchange for “not going down”: You may hear “your money is safe, and it goes up with the stock market but is guaranteed to never go down” for some variable annuities. This has three nefarious aspects to it:

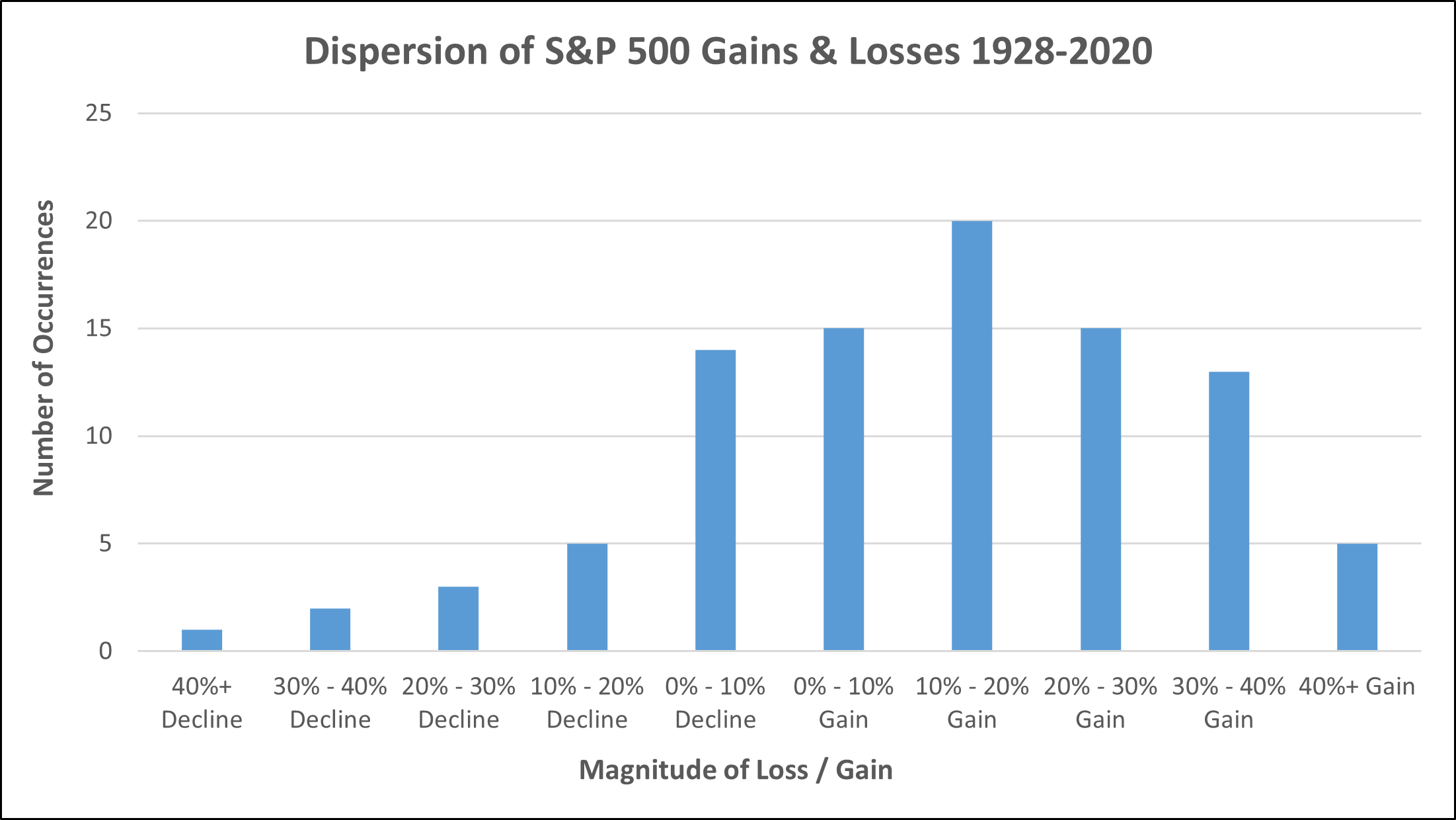

- When your money “goes up” with the stock market, your “upside” is usually capped, meaning you don’t capture the full amount in a year of strong returns. This feature is commonly found in indexed annuities, not variable annuities, which typically track an underlying equity-like investment portfolio. So for the most basic indexed annuities, your money won’t go down when the market goes down, but if the stock market goes up 18% like it did in 2020 or 31% like it did in 2019 your “investment” can “participate” but could be capped at something like 8%. This begs the question: What is the historical record on different types of returns? According to a database compiled by New York University (NYU) “making the bet” on the stock market not going down is very much in favor of the insurance company. As noted in the chart below, between 1928 and 2020, the S&P 500 finished with a positive return in 73% of all years. Taking this one step further, only 12% of all years saw the S&P 500 decline more than 10%. This severe decline (greater than 10%) is typically what an annuity buyer sees as so valuable, and it can be. But it has historically been a rarity and an expensive event to insure against, at least since 1928.

Source: New York University

- What about dividends? For many indexed annuities checking the fine print is again critical as many keep the cash payments for themselves (for annuity reserves) while the investor typically only benefits from price appreciation of the underlying index. Again, this is most common with index annuities, as variable annuities typically are credited with price appreciation and investment income. This may seem like a minor annoyance with the S&P 500 currently yielding about 1.3%. But historically, dividends have been a significant contributor to total return. According to a recent study by Hartford Funds (https://www.hartfordfunds.com/dam/en/docs/pub/whitepapers/WP106.pdf), since the 1970’s, 84% of the total return of the S&P 500 can be attributed to reinvesting dividends and the compounding effect of the reinvestment. Taking the longer view, between 1930 and 2020, dividends contributed about 41% of the total return of the S&P 500. Clearly the insurance company benefits in situations where they cash in the premium, investing a portion in equities, and only promise capped price appreciation to the annuitant.

- Nothing is guaranteed: Regardless of the advertisements from the insurance companies, nothing is guaranteed. If an insurance company goes out of business because they were selling high-payout annuities and could not make good on those payments, then the annuitant can be left holding the bag. There are no guarantees. This concept is usually buried in the fine print in what could be a contract consisting of a two-inch stack of documents.

As one might expect, these statistics are never cited on the radio and internet advertisements.

Annuities are Complicated: Looking at an annuity contract can be overwhelming. Most look like a small print version of Tolstoy’s War & Peace. While perfectly legal and regulated, the length and complexity speak to how difficult it can be to clearly evaluate the costs versus the benefits. As usual, the devil is in the details on these contracts, and the greater the complexity, the less able we are to adequately judge the value. In our experience helping clients evaluating these products, we’ve found the complexity and voluminous provisions make them almost impossible to comprehend. And when we’ve called the insurance company for help, the person on the other end of the 1-800 number isn’t usually trained or experienced, offering little help. Adding to the complexity are tax planning issues associated with owning an annuity. The owner must understand the consequences of surrendering, taking distributions, how much of a return is taxed at ordinary income tax rates, and the absence of step up in cost basis. Just understanding the contract itself is difficult, but the ramifications for the tax return also require detailed analysis.

THE GOOD

Despite all the bad aspects of annuities, some can serve a limited purpose for some people.

“Peace of Mind”: One could argue there is value with the peace of mind in knowing fixed expenses in retirement would be covered by a combination of social security and annuity payments. While this is expensive peace-of-mind, for some folks it’s worth it. We don’t reflexively eliminate annuities from consideration for our clients, but it’s not our main focus. As a reminder, we do not sell annuities or any other financial products. This allows us to maintain our objectivity when advising clients. But if a client does see the value of these high-cost guarantees, we can reach out to trusted third party providers to help fulfill this need. Most importantly, we would integrate this income stream into the broader investment, tax, and estate plan so that we structure the other pillars of the plan appropriately.

Mortality Credits help with “returns”: When thousands of people contract with an insurance company through annuities, the insurance company is playing the percentages and usually forecasting some people are going to die early – and they are statistically correct. This calculated bet allows for the insurance company to afford higher payouts than just passing through the premium payments of the annuitants, net of costs, and fees.

Some low-cost options available: Not all annuities are high-fee and high-commission. There are low-cost options that can make sense if the circumstances call for an annuity. Very often, these buyers value safety and security above all else, and while expensive, the value derived from these products can be intensely personal.

THE UGLY

Unfortunately, we still hear ugly stories of these products being aggressively pushed on people, especially older people who may not know better. There are many such stories of elderly people handing over a large sum of money in exchange for “guaranteed payments for life.” Most of those products come with a 7-year surrender period. Does that really make sense?

Are Annuities a Good Investment?

Bottom Line: Overall, for select and limited situations annuities can make sense. But like many financial products, annuities are often “sold, not bought,” leading to confusion and unmet expectations. Understanding the pros and cons in all their detail is key to making a confident, informed decision.